Catch-22

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Catch-22 (disambiguation).

| Catch-22 | |

|---|---|

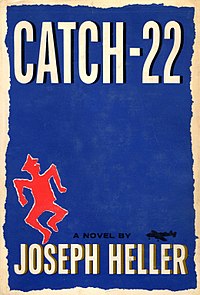

First edition cover |

|

| Author(s) | Joseph Heller |

| Cover artist | Paul Bacon[1] |

| Country | USA |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Black humor, absurdist fiction, satire, war fiction, historical fiction |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster |

| Publication date | 11 November 1961 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 453 pp (1st edition hardback) |

| ISBN | 0-684-83339-5 |

| Dewey Decimal | 813/.54 22 |

| Followed by | Closing Time (1994) |

The novel follows Captain John Yossarian, a U.S. Army Air Forces B-25 bombardier. Most of the events in the book occur while the fictional 256th squadron is based on the island of Pianosa, in the Mediterranean Sea west of Italy. The novel looks into the experiences of Yossarian and the other airmen in the camp, and their attempts to keep their sanity in order to fulfill their service requirements, so that they can return home. The phrase "Catch-22", "a problematic situation for which the only solution is denied by a circumstance inherent in the problem or by a rule,"[4] has entered the English language.

Contents |

Concept

Among other things, Catch-22 is a general critique of bureaucratic operation and reasoning. Resulting from its specific use in the book, the phrase "Catch-22" is common idiomatic usage meaning "a no-win situation" or "a double bind" of any type. Within the book, "Catch-22" is a military rule, the self-contradictory circular logic that, for example, prevents anyone from avoiding combat missions. The narrator explains:There was only one catch and that was Catch-22, which specified that a concern for one's safety in the face of dangers that were real and immediate was the process of a rational mind. Orr was crazy and could be grounded. All he had to do was ask; and as soon as he did, he would no longer be crazy and would have to fly more missions. Orr would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn't, but if he were sane he had to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn't have to; but if he didn't want to he was sane and had to. Yossarian was moved very deeply by the absolute simplicity of this clause of Catch-22 and let out a respectful whistle. (p. 56, ch. 5)Other forms of Catch-22 are invoked throughout the novel to justify various bureaucratic actions. At one point, victims of harassment by military police quote the MPs' explanation of one of Catch-22's provisions: "Catch-22 states that agents enforcing Catch-22 need not prove that Catch-22 actually contains whatever provision the accused violator is accused of violating." Another character explains: "Catch-22 says they have a right to do anything we can't stop them from doing."

Yossarian comes to realize that Catch-22 does not actually exist, but because the powers that be claim it does, and the world believes it does, it nevertheless has potent effects. Indeed, because it does not exist, there is no way it can be repealed, undone, overthrown, or denounced. The combination of force with specious and spurious legalistic justification is one of the book's primary motifs.

The motif of bureaucratic absurdity is further explored in 1994's Closing Time, Heller's sequel to Catch-22. This darker, slower-paced, apocalyptic novel explores the pre- and post-war lives of some of the major characters in Catch-22, with particular emphasis on the relationship between Yossarian and tailgunner Sammy Singer.

Synopsis

| This section requires expansion. (June 2008) |

While the first five parts "sections" develop the novel in the present and through use of flash-backs, the novel significantly darkens in chapters 32–41. Previously the reader had been cushioned from experiencing the full horror of events, but now the events are laid bare, allowing the full effect to take place. The horror begins with the attack on the undefended Italian mountain village, with the following chapters involving despair (Doc Daneeka and the Chaplain), disappearance in combat (Orr and Clevinger), disappearance caused by the army (Dunbar) or death (Nately, McWatt, Mudd, Kid Sampson, Dobbs, Chief White Halfoat and Hungry Joe) of most of Yossarian's friends, culminating in the unspeakable horrors of Chapter 39, in particular the rape and murder of Michaela, who represents pure innocence.[5] In Chapter 41, the full details of the gruesome death of Snowden are finally revealed.

Despite this, the novel ends on an upbeat note with Yossarian learning of Orr's miraculous escape to Sweden and Yossarian's pledge to follow him there.

Style

Many events in the book are repeatedly described from differing points of view, so the reader learns more about each event from each iteration, with the new information often completing a joke, the punchline of which was told several chapters previously. The narrative's events are out of sequence, but events are referred to as if the reader is already familiar with them, so that the reader must ultimately piece together a timeline of events. Specific words, phrases, and questions are also repeated frequently, generally to comic effect.Much of Heller's prose in Catch-22 is circular and repetitive, exemplifying in its form the structure of a Catch-22. Heller revels in paradox, for example: "The Texan turned out to be good-natured, generous and likable. In three days no one could stand him", and "The case against Clevinger was open and shut. The only thing missing was something to charge him with." This atmosphere of apparent logical irrationality pervades the book.

While a few characters are most prominent, notably Yossarian and the Chaplain, the majority of named characters are described in detail with fleshed out or multidimensional personas to the extent that there are few if any "minor characters."

Although its non-chronological structure may at first seem aleatoric, Catch 22 is actually highly structured. A structure of free association, ideas run into one another through seemingly random connections. For example, Chapter 1 entitled "The Texan" ends with "everybody but the CID man, who had caught cold from the fighter captain and come down with pneumonia."[6] Chapter 2, entitled "Clevinger", begins with "In a way the CID man was pretty lucky, because outside the hospital the war was still going on."[7] The CID man connects the two chapters like a free association bridge and eventually Chapter 2 flows from the CID man to Clevinger through more free association links.

Themes

|

|

This article may contain original research. (February 2012) |

Another theme is the perversion of notions of right or wrong, particularly patriotism and honor.

Several themes mingle; "that the only way to survive such an insane system is to be insane oneself" comments on Yossarian's answer to the Social dilemma (that he would be a fool to be any other way) and another theme, "that bad men (who sell out others) are more likely to get ahead, rise in rank, and make money," turns our notions of what is estimable on their heads as well.

Yossarian comes to fear his commanding officers more than he fears the Germans attempting to shoot him down and he feels that "they" are "out to get him." Key among the reasons Yossarian fears his commanders more than the enemy is that as he flies more missions, Colonel Cathcart increases the number of required combat missions before a soldier may return home; he reaches the magic number only to have it retroactively raised. He comes to despair of ever getting home and is greatly relieved when he is sent to the hospital for a condition that is almost jaundice. In Yossarian's words: "The enemy is anybody who's going to get you killed, no matter which side he's on, and that includes Colonel Cathcart. And don't you forget that, because the longer you remember it, the longer you might live." [8]

While the military's enemies are Germans, none appear in the story as an enemy combatant. This ironic situation is epitomized in the single appearance of German personnel in the novel, who act as pilots employed by the squadron's Mess Officer, Milo Minderbinder, to bomb the American encampment on Pianosa. This predicament indicates a tension between traditional motives for violence and the modern economic machine, which seems to generate violence simply as another means to profit, quite independent of geographical or ideological constraints. Heller emphasizes the danger of profit seeking by portraying Milo without “evil intent;" Milo’s actions are portrayed as the result of greed, not malice.

No comments:

Post a Comment